You know, part of my joy today is about the Supreme Court's decision on the Affordable Care Act -- but I think its deeper than that.

Its rooted in my sense that the legitimacy of a core American institution (the Court) wavered, even shook, but ultimately remained in place.

I remember the acid in my stomach after the Bush v. Gore decision, and anticipated having the same feeling this morning. The nihilism that American conservatism seems to have adopted seems bent on devouring standards, institutions and processes that have served this country well for a very long time -- like some sort of civic auto-immune disease.

As James Fallows recently wrote, "liberal democracies depend on rules, but also on norms -- on the assumption that you'll go so far, but no further, to advance your political ends. The norms imply some loyalty to the system as a whole that outweighs your immediate partisan interests."

It was out of such loyalty that Gore stepped aside after the Court stopped the vote count in 2000, as much as many of us wanted him to fight. It was in violation of that loyalty that the Bush campaign sought to stop the vote count, and in violation of that loyalty that the Supreme Court's narrow majority upheld Bush's strategy.

It was in support of that loyalty that Chief Justice John Roberts, however reluctantly, ruled today. Perhaps there still are a few true conservatives left among the bomb-throwing crazies, who would undo in the name of patriotism all that makes that patriotism morally justifiable.

Sir Thomas More, as quoted in "A Man for All Seasons":

"And when the last law was down, and the Devil turned 'round on you, where would you hide, ...the laws all being flat? This country is planted thick with laws, from coast to coast, Man's laws, not God's! And if you cut them down..., do you really think you could stand upright in the winds that would blow then? Yes, I'd give the Devil benefit of law, for my own safety's sake!"

Thoughts on politics, cities and the state of American life, culture and economics, from the perspective of a pragmatic lefty historian. "Chants Democratic" comes from "Leaves of Grass" by Walt Whitman, the avatar of American Democracy.

About Me

- Mark Santow

- I am Associate Professor and Chair of the History Department at the University of Massachusetts-Dartmouth. I am also the Academic Director of the Clemente Course in the Humanities, in New Bedford MA. Author of "Social Security and the Middle Class Squeeze" (Praeger, 2005) and the forthcoming "Saul Alinsky the Dilemma of Race in the Post-War City" (University of Chicago Press), my teaching and scholarship focuses on American urban history, social policy, and politics. I am presently writing a book on home ownership in modern America, entitled "Castles Made of Sand? Home Ownership and the American Dream." I live in Providence RI, where I have served on the School Board since March 2015. All opinions posted here are my own.

Thursday, June 28, 2012

America joins the ranks of civilized nations!

Victory! I'd like to take this time to welcome my country to the 20th century, and offer a brief shout out to Franklin Roosevelt, Harry Truman, and every great American who has fought for universal healthcare as a human right.

And thanks, most important, to President Obama -- who saw this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, and grabbed it!

And thanks, most important, to President Obama -- who saw this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, and grabbed it!

Monday, June 25, 2012

A love song for Anthony Kennedy

I just met you, and this is crazy, but here's ObamaCare -- uphold it baby!

[A revision: Kennedy you two-timing so and so, this is for John Roberts instead.]

[A revision: Kennedy you two-timing so and so, this is for John Roberts instead.]

Twiddling my thumbs while waiting for modern liberalism to die

Bloomburg news surveyed 21 top constitutional law professors about the impending Supreme Court decision on the Affordable Care Act. 19 of them said that if the court follows legal precedent, it (the individual mandate) will be upheld.

“The precedent makes this a very easy case,” said Christina Whitman, a University of Michigan law professor. “But the oral argument indicated that the more conservative justices are striving to find a way to strike down the mandate.”

Only 8 of the 21 legal scholars actually expect the mandate to be upheld, despite the clear direction of constitutional precedent.

What does this tell us about the conservative majority on the Court? And the old right-wing saw about liberal activist judges?

18 of the 21 agreed that if the individual mandate is overturned on a 5-4 vote, it will damage the credibility of the Court itself.

“When you take the fact of a high-profile, enormously controversial and politically salient case -- to have it decided by the narrowest majority with a party-line split looks very bad, it looks like the court is simply an arm of one political party,” University of Chicago Law Professor Dennis Hutchinson said in an interview.

However, I'm not going to despair yet, at 9:23am on Monday June 25th (an announcement could come as soon as 10am). Liberal constitutional lion Bruce Ackerman still believes that conservatives Roberts and Kennedy won't be able to pull the trigger: “I continue to find it extremely unlikely that Justices Roberts and Kennedy will support a 5-4 decision that has such an insubstantial basis in 75 years of Supreme Court case law."

Ackerman, alas, was the only respondent who said the court is very likely to uphold the insurance-coverage requirement -- the opinion that was held by most legal observers across the ideological spectrum, until oral arguments.

Stay tuned....

“The precedent makes this a very easy case,” said Christina Whitman, a University of Michigan law professor. “But the oral argument indicated that the more conservative justices are striving to find a way to strike down the mandate.”

Only 8 of the 21 legal scholars actually expect the mandate to be upheld, despite the clear direction of constitutional precedent.

What does this tell us about the conservative majority on the Court? And the old right-wing saw about liberal activist judges?

18 of the 21 agreed that if the individual mandate is overturned on a 5-4 vote, it will damage the credibility of the Court itself.

“When you take the fact of a high-profile, enormously controversial and politically salient case -- to have it decided by the narrowest majority with a party-line split looks very bad, it looks like the court is simply an arm of one political party,” University of Chicago Law Professor Dennis Hutchinson said in an interview.

However, I'm not going to despair yet, at 9:23am on Monday June 25th (an announcement could come as soon as 10am). Liberal constitutional lion Bruce Ackerman still believes that conservatives Roberts and Kennedy won't be able to pull the trigger: “I continue to find it extremely unlikely that Justices Roberts and Kennedy will support a 5-4 decision that has such an insubstantial basis in 75 years of Supreme Court case law."

Ackerman, alas, was the only respondent who said the court is very likely to uphold the insurance-coverage requirement -- the opinion that was held by most legal observers across the ideological spectrum, until oral arguments.

Stay tuned....

Tuesday, June 12, 2012

Race, generational politics, and the Democrats great opportunity

The whitening of the Republican Party, and the great white Boomer estate sale

In the June 7th 2012 online edition of the New York Times, columnist Charles Blow broke down the findings of the recent Pew Research Center American Values survey along racial lines.

Blow points to 3 important findings:

First, since 2000, while the percentage of GOP supporters that are white has remained steady (87%), the percentage of Democrats who are white has fallen from 64% to 55%. Interestingly, the racial breakdown of 'independents' has also changed -- from 79% white in 2000, to 67% white in 2012.Blow's conclusion: "if current trends persist, in a few years the Democratic Party will be a majority minority party."

Second, whites, blacks and Latinos often have very different views about poverty, opportunity and the role of government.Blow's conclusion: because the Democrats are increasingly diverse racially (blacks, Latinos), while the Republicans are not, these racially divergent views are going to profoundly affect the national debate in this election year.

Third, swing voters (those who are undecided, who lean towards a candidate, or who say that they could change their mind) are overwhelmingly and disproportionately white (nearly 3/4). Pew found that these voters lean more towards Obama on issues like civil liberties and the role of labor unions, but are closer to Romney on the social safety net, immigration, and affirmative action.Blow's conclusion here is implied rather than stated, but the implication is pretty clear: Obama will lose if the focus of the 2012 campaign is on these 'racially charged issues.' The deeper implication is that the GOP would benefit from a campaign that is focused on these things.

I don't have any major quibbles with Blow's analysis, though some of the data he cites really pushes one towards a more radical conclusion, one which he didn't hint at, even obliquely:

As the Democratic Party slowly begins to reflect the demographic changes underway in the country (in its constituencies, if not yet in its positions), the Republican Party is increasingly becoming the Defense of White Privilege Party, and its short-term electoral interests are leading it even further in that direction.Of course, behind the curtain an awful lot of what Republican policymakers actually do has much more to do with the protection of capital (particularly financial capital) than the protection of white privilege per se -- but the nudges, winks and dog whistles, particularly for the Tea Party folks, are often racially inflected.

And if the GOP's defense of the current structure of American wealth (and its defunding of those institutions which might offer wider access to it or challenge it) isn't at the same time a defense of a certain kind of white privilege, what is it? If those who have climbed the ladder are overwhelmingly white, and you pull the ladder up behind you, what (who) have you defended? There is no reason to think that because the Party houses within it a supposedly cosmopolitan financial elite and an aging coalition of economically and racially insecure whites, that these differences will somehow temper the racial nature of its appeal. For most of the history of our country, corporate and financial interests have been entirely comfortable and compatible with a white supremacist politics.

Almost every major policy position the Republican Party now takes will work to the benefit of white voters, and to the detriment of citizens of color. Attacks on public employee unions and Paul Ryan's call for massive cuts in non-defense spending has (and will) disproportionately affect black and Hispanic workers. Likewise with pay freezes for public workers, and pension and health insurance cutbacks. All of this constitutes an assault on a black middle class that has already seen billions of dollars of its wealth stripped away by sub-prime lending and the collapse of the housing market -- with these things, in turn, enabled by financial deregulation and the refusal to meaningfully address housing discrimination and residential segregation.

Democrats may try to take some comfort in the belief the GOP's coalition of cosmopolitan financial capital and economically and racially insecure whites will inevitably blow apart, as the latter gradually begins to see what is truly 'the matter with Kansas.' This comfort, however, is misplaced -- at least in the short-term. What holds this coalition together at the moment is a unifying hostility to the nature and reach of the modern American state. Financial elites largely maintain the same position on this issue that they have since they wormed their way into the Republican Party in the 1860s and 1870s: government should be small and weak, except when it aids in the accumulation of capital, and protects it against internal and external competition. Insecure whites, particularly those who increasingly affiliate themselves with the Tea Party, believe that the young, the lazy and the dark are parasitically living off of the hard work of whites -- aided by President Obama.

Of course, the GOP hostility to government (and labor) as a counterweight to concentrated economic power and the inherent vicissitudes of life in a market society directly challenges the civil and social rights that have enabled whatever progress toward racial justice we've achieved in the past half-century. A government with such a diminished reach inevitably comforts the comfortable, and afflicts the afflicted. That it will afflict a large number of white Americans too -- particularly the young -- is clear. The future of the country will depend upon whether these white Americans will answer the GOP's racial siren song, or make common cause with their fellow citizens who represent the nation's demographic future.

While at first blush all of this seems to be about fiscal conservatism, it really isn't. You can't balance budgets or grow the economy (or govern effectively and justly) with massive tax cuts, and greatly diminished public investments in infrastructure, institutions, and people. Not only is the GOP no longer the party of Teddy Roosevelt; it isn't even the party of its Whiggish predecessor Henry Clay.

But more revealing is the nature of the rhetoric on the Right: we have witnessed the revival of the racially-tinged language of "government dependency," courtesy of the Tea Party.

Blow notes that a remarkable 90% (!) of Romney's supporters are white (87% of Republicans are), and that white independents also move into the Romney camp when the focus is on social programs and immigration, which he describes as 'racially charged issues.'

There is no inherent reason why the discussion of social programs during the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression should be 'racial' in nature, particularly since the vast majority of poor Americans are white, and whites are by far the greatest beneficiaries of the welfare state. Immigration isn't inherently a 'racially charged' issue either; it is a demographic issue, perhaps, but the push and pull factors that shape the flow of immigration are largely economic.

The deeper question is this: what makes the social safety net and immigration 'racially charged' issues? Perhaps this is obvious, but it needs to be stated: it is white Americans who make these subjects 'racial.' Not blacks, not Latinos, not liberals, and not Democrats. Whites.

It is well known that by the middle of this century, 'whites' (as Americans have come to define them since World War II) will no longer constitute a majority of the population of the United States. In many places, this has either already happened, or soon will. On the eve of the financial crash, the U.S. Census Bureau announced that non-Hispanic whites would become a minority in the country in 2042, eight years earlier than had previously been estimated.

The collision of the Great Recession with demographic change has lent our already-polarized national politics a discomforting flavor of racial apocalypse, diverting many Americans -- and most of the Republican Party -- away from the inequalities that truly matter, and toward a paranoid defense of the favored racial quarter. We can see this in our daily lives, as American metropolitan areas re-segregate by race, while economic segregation metastasizes across the national landscape. We can see it in the racialized rhetoric of the Tea Party. And we can see it in the 'pull-up-the-ladder-of-opportunity' policies that the GOP increasingly recommends.

White Americans, of course, aren't monolithic. The Pew Survey makes clear that while a lot of whites seem to be hunkering down in the Republicans' racial redoubt (particularly older whites), those who continue to define themselves as Democrats increasingly share the views of most blacks and Latinos not only on economics, opportunity and the role of government, but also on the issues of immigration, affirmative action and social programs. The Survey indicates that this is particularly true for younger white voters.

The percentage of Republicans calling for "tighter immigration controls" has ticked slightly upward over the past twenty year, from 78% to 84%. There has, however, been a decided downward shift in opinions among Democrats, reflecting both demographic reality and a growing recognition of that reality by their white constituents, regardless of ideology or education. In 1992 there was basically no partisan gap on the issue; today, only 58% of Democrats think we need a more restrictive immigration policy, down from 74% in 1992. While independent voters are more favorably disposed toward tighter controls than Democrats are, the trend is largely downward -- reinforcing my point above, about the increasingly racialized GOP.

From the Survey:

In 1992, Republican and Democratic perceptions of the 'threat' immigrants posed to American values differed little; voters in each party were evenly split. Today, there is a substantial gap: 60% of Republicans believe that immigrants pose such a threat, while just 39% of Democrats do. Indeed, regardless of ideology or education, Democrats do not perceive immigrants as a threat, though the numbers do vary; the exact opposite is the case among Republicans.

There also seems to be an age correlation. While those between 18-29 and 30-49 are (for lack of a better term) 'pro' immigrant, older voters are not.

According to the Survey, Tea Party Republicans and Tea Party-leaning independents both seem to be more likely to be hostile to immigrants and skeptical of the persistence of racial discrimination than do Republicans more generally.

In other words, the Tea Party is a force for the continuing racialization of the GOP, as much as its most prominent advocates wish to deny it.

The GOP has effectively become the anti-immigrant party, as Thomas Edsall noted recently. Its constituents will not support candidates perceived as 'pro-immigrant,' as John McCain discovered in 2010. And within the larger context of economic insecurity -- when employment appears to be a zero-sum game -- immigration has also become an effective wedge issue for the Republicans. In 2010 and again this year, they are using it to appeal to economically stressed moderate white Democrats, who fear that immigrants are siphoning off jobs, tax dollars and public benefits, and that all of this has been enabled by the self-evidently 'foreign' Barack Obama. This of course ignores stacks of research indicating that immigrants are vital to the economic health of the country, and to the long-term viability of the very entitlement programs the Republicans say they are depleting. Indeed, the greatest threat to Social Security and Medicare is posed by the very candidates Tea Party voters support.

The Republican House vote margin among whites in 2010 (62% to 38%) was higher than in any House election since 1968, when exit polling first began. The GOP is shoving all of its white chips to the center of the table.

For Democrats, there is an optimistic scenario that can be drawn from this. There is also a dangerous -- even catastrophic -- one that can also be drawn. The damage inflicted by the latter would extend far beyond partisan imbalances, and do permanent harm to our democracy.

The more positive one, to be blunt, is that the combination of demographic change and the GOPs over-reaction to the demands of financial capital and the coming death-rattle of white Boomer privilege makes the electoral future of the Democratic Party (or some new party that emerges from it) very bright indeed.

Assuming there is anything left to inherit, once the White Baby Boomer Estate Sale has concluded.

What's the negative scenario? That in their effort to 'take their country back' and 'free up' capital to finance that effort, white Republicans will pull the entire structure down around them, diminishing their own future and everyone else's.

Let's start with the scary stuff first, so we can finish on a high note.

Tuesday, June 05, 2012

Solidarity, For Now? Liberalism and the Many Costs of Labor's Decline

Great piece today by Providence's own Joe Nocera, on what the decline of organized labor has done to the American Dream -- and a good day for it, too, as Scott Walker's revolutionary (non-union) train chugs into the Madison Station.

When I moved to RI in 2003 from Washington, I was rather stunned to hear many of my liberal friends repeat the media meme that organized labor was too powerful in the Ocean State [note: I will use the term 'liberal' rather than 'progressive,' because in my experience people on the left my age and younger tend to substitute the latter for the former, without knowing the meaning of either].

My surprise stemmed from two sources: the extent to which liberals of my generation (I'm 45) underestimate the vital importance of unions for the enactment and preservation of liberal measures and attitudes, and the extent to which these same liberals had completely misread the situation in their own state.

On the latter, read Scott McKay's brilliant take-down of the 'union rules RI' meme on NPR the other day. As he notes, would the tax equity bill have gone down to defeat if unions truly ruled the roost?

Just under 18% of Rhode Islanders are represented by labor unions; it was 26% in 1964, and 22.5% in 1984. In other words, the trend is the same here as everywhere: downward.

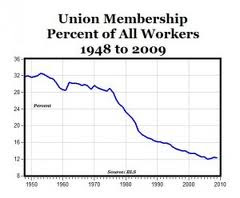

The national trend, since the passage of Taft-Hartley in 1947:

There are many reasons for this decline. Economic change, the shift of American industry and population to the South and Southwest, the restrictive nature of our labor laws, McCarthyism and red-baiting, poor and sometimes corrupt union leadership. Unions were also victims of their own success; by helping to create the post-war middle class, many of their white constituents (and their children) decamped for the suburbs, and resisted seeing the struggles of the black (and eventually, Latino) working class they left behind as similar to their own, rather than a threat. In other words, the American original sin of race infected -- had long infected -- even its most transformational social movements and institutions. Perhaps our individualistic and materialistic culture has also become indifferent -- even hostile -- to the sensibility of solidarity, upon which the labor movement depends.

All of these things have mattered, but the most important cause of labor's decline, ultimately, has been the political success of corporate resistance, particularly since the early 1970s (on this, read Elizabeth Fones-Wolf and Jefferson Cowie, as well as Jacob Hacker and Paul Pierson). Many of my peers (and my students) seem to assume that unions are a thing of the past, and that the victories they won -- like the end of slavery and the enfranchisement of women -- are now written in stone, and we can move on. In other words, progress gave rise to unions, and then tossed them on the scrap heap of history (with the American Anti-Slavery Society, The Women's Party, the NAACP, and affirmative action) when they had fulfilled their role. Events in Wisconsin (and, of course, the Occupy movement) may have finally awoken at least some of these folks to the possibility that if the ship of history has moved in this direction, it may be because someone is steering it there.

As a labor historian and former organizer, I also had a hard time getting my head around the idea that unions could actually be too powerful -- both because I can't imagine that being the case anywhere in 21st America, and because I can't imagine that being a negative thing, on balance. I would love to have to grapple with that problem, here and nationally.

Walter Reuther, vampire-killer...or life raft?

So why does the decline of labor matter, in Rhode Island and nationally?

Well for one, it is hard not to be struck by the apparent correlation between the decline of union power, and the emergence of increasing inequality, economic insecurity, and wage stagnation for large portions of our population since the early 1970s. From 1940 until the early 70s, the economic benefits of the productivity of the American economy were widely shared, leading to what economists have called 'the Great Convergence': a shrinking of income inequality, combined with a strong and steady increase in the standard of living for the vast majority of the population.

But since then?

So where did all that money go? Did it go to those wealth-sucking and budget-busting public employees that Scott Walker keeps going on about? Did those tax-and-spend liberals devour all of it, so they could rain manna on their special interest constituencies?

Um, no.

Is it any wonder why vampire stories seem to have captured the cultural zeitgeist?

When I moved to RI in 2003 from Washington, I was rather stunned to hear many of my liberal friends repeat the media meme that organized labor was too powerful in the Ocean State [note: I will use the term 'liberal' rather than 'progressive,' because in my experience people on the left my age and younger tend to substitute the latter for the former, without knowing the meaning of either].

My surprise stemmed from two sources: the extent to which liberals of my generation (I'm 45) underestimate the vital importance of unions for the enactment and preservation of liberal measures and attitudes, and the extent to which these same liberals had completely misread the situation in their own state.

On the latter, read Scott McKay's brilliant take-down of the 'union rules RI' meme on NPR the other day. As he notes, would the tax equity bill have gone down to defeat if unions truly ruled the roost?

Just under 18% of Rhode Islanders are represented by labor unions; it was 26% in 1964, and 22.5% in 1984. In other words, the trend is the same here as everywhere: downward.

The national trend, since the passage of Taft-Hartley in 1947:

The breakdown by state, since 1964:

There are many reasons for this decline. Economic change, the shift of American industry and population to the South and Southwest, the restrictive nature of our labor laws, McCarthyism and red-baiting, poor and sometimes corrupt union leadership. Unions were also victims of their own success; by helping to create the post-war middle class, many of their white constituents (and their children) decamped for the suburbs, and resisted seeing the struggles of the black (and eventually, Latino) working class they left behind as similar to their own, rather than a threat. In other words, the American original sin of race infected -- had long infected -- even its most transformational social movements and institutions. Perhaps our individualistic and materialistic culture has also become indifferent -- even hostile -- to the sensibility of solidarity, upon which the labor movement depends.

All of these things have mattered, but the most important cause of labor's decline, ultimately, has been the political success of corporate resistance, particularly since the early 1970s (on this, read Elizabeth Fones-Wolf and Jefferson Cowie, as well as Jacob Hacker and Paul Pierson). Many of my peers (and my students) seem to assume that unions are a thing of the past, and that the victories they won -- like the end of slavery and the enfranchisement of women -- are now written in stone, and we can move on. In other words, progress gave rise to unions, and then tossed them on the scrap heap of history (with the American Anti-Slavery Society, The Women's Party, the NAACP, and affirmative action) when they had fulfilled their role. Events in Wisconsin (and, of course, the Occupy movement) may have finally awoken at least some of these folks to the possibility that if the ship of history has moved in this direction, it may be because someone is steering it there.

As a labor historian and former organizer, I also had a hard time getting my head around the idea that unions could actually be too powerful -- both because I can't imagine that being the case anywhere in 21st America, and because I can't imagine that being a negative thing, on balance. I would love to have to grapple with that problem, here and nationally.

Walter Reuther, vampire-killer...or life raft?

So why does the decline of labor matter, in Rhode Island and nationally?

Well for one, it is hard not to be struck by the apparent correlation between the decline of union power, and the emergence of increasing inequality, economic insecurity, and wage stagnation for large portions of our population since the early 1970s. From 1940 until the early 70s, the economic benefits of the productivity of the American economy were widely shared, leading to what economists have called 'the Great Convergence': a shrinking of income inequality, combined with a strong and steady increase in the standard of living for the vast majority of the population.

But since then?

So where did all that money go? Did it go to those wealth-sucking and budget-busting public employees that Scott Walker keeps going on about? Did those tax-and-spend liberals devour all of it, so they could rain manna on their special interest constituencies?

Um, no.

Is it any wonder why vampire stories seem to have captured the cultural zeitgeist?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)